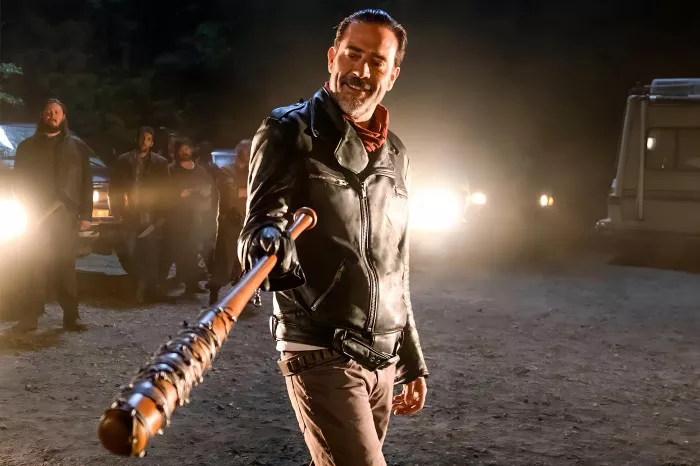

Negan, the charismatic and ruthless leader of the Saviors in “The Walking Dead,” is known for his colorful language and distinctive way of addressing the undead, commonly referred to as walkers in the series. However, Negan has his own unique lexicon for describing these flesh-eating creatures, adding depth and character to his interactions with both allies and enemies. In this article, we will delve into what Negan calls walkers in “The Walking Dead,” exploring the significance of his terminology and its impact on the narrative.

Negan’s Lexicon

- “Walkers”: While Negan occasionally uses the term “walkers” to refer to the undead, he often employs more colorful and imaginative language to describe these flesh-eating creatures. Despite its prevalence in the series, “walkers” is a relatively neutral and generic term, lacking the personal flair and character associated with Negan’s unique vocabulary.

- “St Eaters”: One of Negan’s favorite terms for walkers is “st eaters,” a derogatory and dehumanizing epithet that underscores his contempt for the undead. By referring to walkers in such a disparaging manner, Negan diminishes their significance and reinforces his own superiority as a living human being. This term also serves to dehumanize the undead, making it easier for Negan and his followers to justify their ruthless actions against them.

- “Skinbags”: Another term used by Negan to describe walkers is “skinbags,” a derogatory reference to their rotting and decayed appearance. This term emphasizes the physical characteristics of the undead, highlighting their grotesque and repulsive nature. By likening walkers to empty vessels or sacks of skin, Negan underscores their lack of humanity and reinforces his own perception of them as disposable and insignificant.

- “Dead Ones”: Negan occasionally refers to walkers simply as “dead ones,” a straightforward and matter-of-fact description of their status as reanimated corpses. While less colorful than some of his other terms, “dead ones” effectively conveys the grim reality of the undead apocalypse and the omnipresent threat posed by the walking dead.

- “Biters”: In some instances, Negan uses the term “biters” to describe walkers, referencing their primary method of attack and transmission of the virus. By focusing on their propensity for biting and infecting living humans, Negan highlights the dangers posed by the undead and underscores the importance of vigilance and caution in the face of the apocalypse.

Significance and Impact

Negan’s unique lexicon for describing walkers in “The Walking Dead” serves several important narrative functions within the series.

- Characterization: Negan’s choice of language reflects his personality and worldview, providing insight into his motivations, attitudes, and beliefs. His use of colorful and derogatory terms to describe walkers reflects his disdain for the undead and his unwavering commitment to survival at any cost.

- World-Building: Negan’s lexicon contributes to the immersive world-building of “The Walking Dead,” adding depth and texture to the post-apocalyptic landscape. His distinctive way of speaking distinguishes him from other characters and reinforces the brutal and unforgiving nature of the world he inhabits.

- Emotional Impact: The language used by Negan to describe walkers evokes strong emotional reactions from both characters and viewers alike. His derogatory and dehumanizing terms serve to devalue the lives of the undead, making it easier for him and his followers to justify their ruthless actions against them.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Negan’s lexicon for describing walkers in “The Walking Dead” is a reflection of his personality, worldview, and the harsh realities of the post-apocalyptic world. His use of colorful and derogatory language serves to dehumanize the undead and reinforce his own superiority as a living human being. By examining Negan’s terminology, we gain insight into his character and motivations, while also gaining a deeper understanding of the narrative and thematic elements of “The Walking Dead.”

https://www.rnada.com/archives/12530